Erbazzone, a rustic pie from the Emilian Apennines

And the gentle revolution of side dishes: from secondary characters to stars of the table

Erbazzone was once a staple for breakfast and dinner; today, it serves as a snack, main course, appetizer, or side dish. It is a rustic pie filled with herbs wrapped in a dough as thin as a veil.

Together with cappelletti, it is one of the gastronomic symbols of Reggio Emilia. The city where the Italian flag was born.

Erbazzone was the main dish for breakfast or dinner that farmers in the Reggio Emilia area would eat with radicchio salad or other wild greens, accompanied by hard-boiled eggs.

This homemade dish is part of the enormous repertoire of Italian cucina povera.

But cucina povera doesn’t mean tout court vegetarian or vegan cuisine.

The cucina povera dishes originated from the need to cook with little. The presence of lard, meat, or bones depended on economic conditions. For this reason, many recipes from the so-called cucina povera, encompassing both peasant and popular cuisine, are vegetarian or vegan. Or they call for such a small amount of lard that it can easily be replaced with olive oil without significantly changing the recipe's structure (though the flavor will be different).

Erbazzone had and has two main characteristics: a filling of herbs enclosed in a dough made from water and flour. However, it was not vegan or vegetarian. In fact, the recipe included lard in the dough and filling.

That said, the vegetarian (and vegan) version has a flavor that is just as interesting as the classic recipe.

Since you can find the traditional recipe on my blog Tortellini&CO, with Swiss chard and pancetta in the filling and lard in the dough, I decided to share a vegetarian variation in this newsletter (if you don't use the Parmesan cheese, it will also be vegan). Furthermore, this is also an ancient version that I hope will inspire you.

In Italy, radicchio is an autumn and winter vegetable now harvested all year round. Spring varieties are also perfect.

The filling of erbazzone best tells its story as an herb pie that originated in mountain farming.

In the past, the filling was not established. The herbs changed with the seasons, depending on what grew spontaneously in front of the house. The same was true for onions or spring onions (the latter were used in the spring). Garlic was sometimes added and sometimes not. Erbazzone with Swiss chard, perhaps the most common variant today, was traditionally made from June to All Saints' Day, a popular saying that indicates the warm season when Swiss chard is available.

From La cucina povera dell'Emilia-Romagna:

The onion and lard are chopped with a heavy knife and placed in an earthen pan to sauté while the erbette (some people mean Swiss chard, others spinach, but in Reggio Emilia someone insist on the existence of erbette) are boiling.

They are then drained and added to the lard and onion mixture to absorb any remaining water, along with a little of breadcrumbs.

When everything has cooled, the grated cheese is added.

The filling was then spread on a sheet of approximately three millimeters thick pastry dough, and the erbazzone was placed in a baking dish measuring up to thirty centimeters in width.

In addition to flour and salt, the dough also contained a small amount of lard, which made it shortcrust.

After arranging the erbazzone dough in the baking pan, once rolled out, it must leave enough space around the edges to cover the herb filling, which should be about two centimeters thick. Add a few lard cubes on the surface, then bake for about 20 minutes.

This dish has many variations that are still practiced today in the Reggio Emilia area, from the Apennines to the Po River.

However, it was once the heart of breakfast or dinner, accompanied only by radicchio, sprelle, or riccioni (from January to March) in a salad with hard-boiled eggs.

Erbazzone originated in the mountains and then spread to the city, first reaching Reggio Emilia and, then, the villages along the Po River. In this way, its history also became linked to that of the great river (as, once, it was called), which, like the Via Emilia, is one of the two main roads of Emilia-Romagna.

I was born and raised with piadina Romagnola, and I discovered erbazzone by chance when I was already in my twenties. This story will make you smile. I ate my first erbazzone in a former convent in Bertinoro, a charming hillside village in Romagna famous for piadina and Sangiovese wine.

The erbazzone, however, was authentic from Reggio Emilia.

At that time, the old building served as a guesthouse where I stayed while attending a master's course. For almost a year, every Sunday evening, my friend Alessandra would return from home in Reggio Emilia with a piece of erbazzone made by her nonna. It was still warm, and we ate it in silence, sitting on the bed in a room that still resembled the spartan monastic cell of yesteryear.

Flavors are like people; they leave a mark on your memory.

Scarpazzone or erbazzone

In Virgil's bucolic poem Moretum, the author notices a herb and cheese pie enclosed between two layers of unleavened bread dough. While it is well known that the ancient Romans enjoyed herb pies, erbazzone certainly has ancient origins, albeit much more recent ones.

Some people refer to this pie as erbazzone, while others call it scarpazzone. Before becoming famous as erbazzone, it was called scarpazzone.

The two terms refer to the same dish. Erbazzone refers to the herbs used in the filling, which used to be Swiss chard, spinach, but also radicchio and other wild herbs; scarpazzone refers to the white stem of Swiss chard, known as scarpa (shoe), which peasant families did not waste and used in the filling after removing the tougher fibers.

I, too, use Swiss chard stems.

As told, there are many variations of this dish.

Not just chard. For example, there is a mountain version made with radicchio and rice. This recipe dates back to a time when women, known as mondine from the Italian verb mondare (to clean), left their homes to work as seasonal rice weeders in the rice fields from March to October. And since the pay was very modest, the landowners added a bag of rice to their wages, which they used once home, mixed with whatever they had, certainly chard or other herbs, but also lard, Parmesan cheese, ricotta, and even eggs.

My radicchio and rice erbazzone is a tribute to the Via Emilia and its people.

From one-dish eaten at dawn or as dinner, before starting or after finishing a hard day's work, erbazzone became, in the 1950s and 1960s, the unpretentious spuntino on occasion of bicycle trips along the Emilian banks of the Po River.

Today, aperitifs have replaced snacks, although some people still eat erbazzone for breakfast or as a mid-morning snack that can be enjoyed at the bar or purchased at the bakery, already cut into pieces.

Yesterday, as today, it is right for convivial lunches. You can use it as an appetizer, a main course, or a side dish.

It's a perfect one dish meal to serve with a couple of sides.

Kitchen notes:

You can also use Swiss chard and spinach with the vegetarian/vegan dough.

For a vegan erbazzone, replace the Parmigiano with another vegan cheese.

The olive oil-based dough is a little less elastic than the traditional dough with lard, but it is still easy to roll out. If it happens to break the dough, don't worry; close the holes by joining the edges of the dough together.

Radicchio and rice erbazzone pie

rectangular baking dish 25x20cm

serves 4-6

Ingredients

Filling

800 g radicchio

100 g spring onion or leek or onion

5 g parsley

100 g Carnaroli rice

100 ml of water

100 g grated Parmigiano or other vegan substitute

salt and olive oil to taste

Dough

300 g all-purpose flour

3 g salt

30 g olive oil

100 ml lukewarm water

Method

Filling

Wash the radicchio, remove the outer leaves and the base of the head, slice thinly, and set aside.

Chop the parsley and spring onion with a knife.

Gently sauté the chopped parsley and spring onion in a pan with a bit of olive oil and a pinch of salt for a few minutes.

Add the rice, stir, then pour in 100 ml of water. Stir again and add the radicchio.

Cook for about 10 minutes or until the radicchio is tender, stirring occasionally. Then, remove the pan from the heat and let it cool.

Now, incorporate Parmigiano stirring.

Taste and season with salt if needed, then mix well.

If the filling seems a little watery, correct some breadcrumbs.

Dough

Place the flour into a bowl and make a well in the center for the salt and oil.

Mix with a metal spoon or fork, adding the water a little at a time to the center. If the flour absorbs a lot of water, add another 50 ml of water, a little at a time.

When the dough begins to take shape, transfer it to a floured surface and knead for a few minutes.

Cover the dough with a bowl or a kitchen towel and let it rest for 30 minutes at room temperature.

Preheat the oven to 180°C (356F).

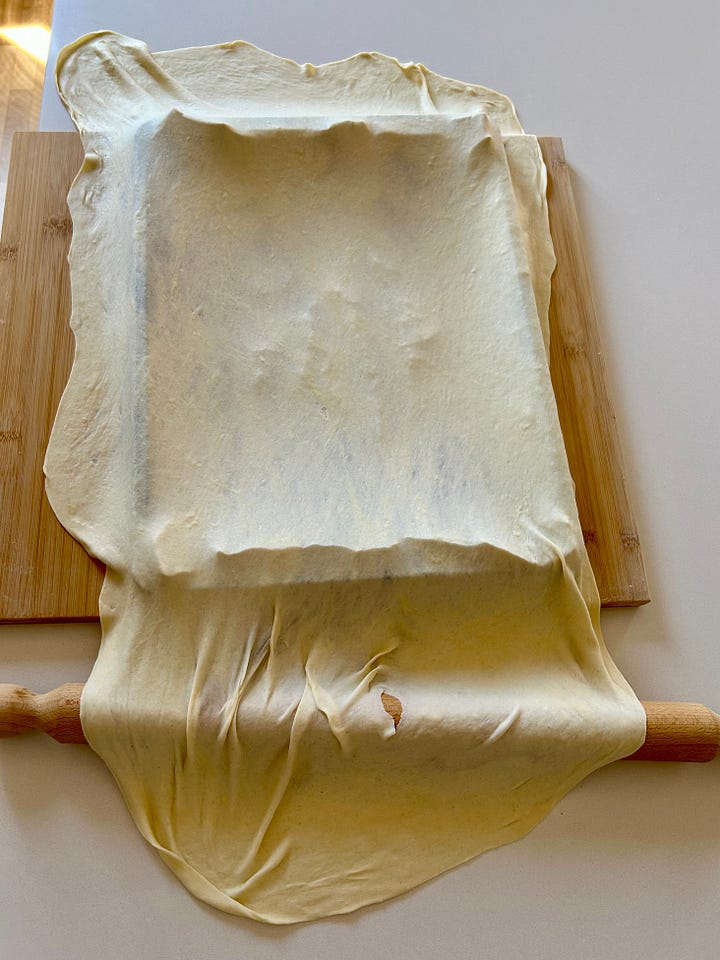

Roll out the dough with a small rolling pin. When it enlarges, roll outward from the center. Turn the dough 45 degrees every two or three strokes of the rolling pin. When it is wide and thin enough, gently pull it with your hands to spread it further and make it thinner (about 3 mm).

This dough is quite elastic, so don't be afraid to break it. If it does, close the hole by matching the edges of the dough.

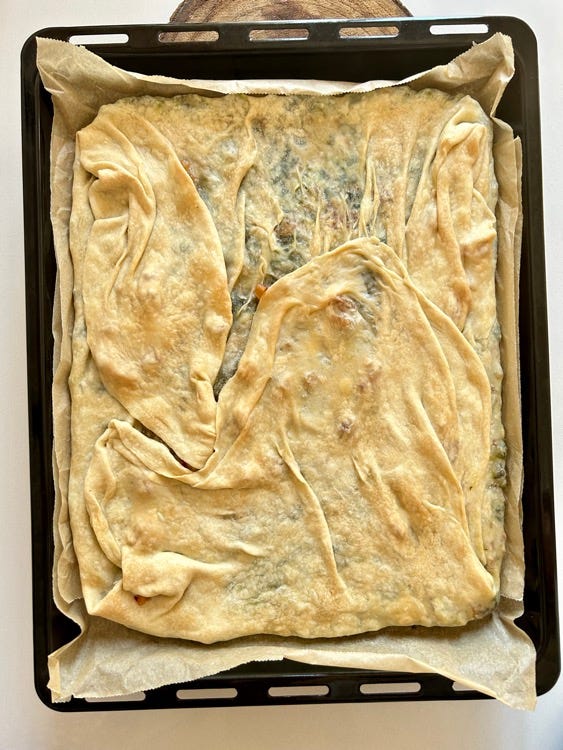

Place the base of erbazzone in a baking pan lined with parchment paper, leaving the edges beyond the mold. Spread the filling to a height of 1 or 2 cm.

Cover the filling with the excess dough, creating folds and gently pulling the dough with your hands to seal the filling.

Prick the surface with the prongs of a fork and brush with olive oil.

Bake for 40 minutes or until the dough is golden brown.

About sides

Take salads, for example. They belong to the side dish category but are increasingly served as one dish.

You've probably noticed that something extraordinary has happened on our tables. Side dishes, which used to accompany the main course, which was usually a roast, have now become the stars.

Recently, I have discovered a great love for these dishes, and my table is becoming a triumph of sides. Not just everyday meals, where dinner almost always consists of two different vegetable dishes.

Even my lunches with friends and family celebrate the richness of the table laid with sides. Recipes designed to create a harmonious symphony of flavors.

More and more often, I forego the main course in favor of setting a table that allows guests to compose the dishes according to their tastes, even though everyone is eating the same things. This lightens the menu, and when dessert arrives, it is a celebration rather than a fatal blow.

These considerations gave shape to Chapter 7, Salads and Side Dishes, of the cookbook that paying subscribers are receiving.

The annual subscription for the newsletter is just over €24, that is the cost of a cookbook. Mine will have nine chapters and lots of recipes! You can also give a subscription as a gift to someone who you think would enjoy this newsletter.