The invisible network of women before the web: friendship, connections and cookbooks

plus a dish of crostini misti, convivial and vegetarian

Despite the rain and cold, March started off in the best way possible, with a visit from a dear friend who lives far away. We didn't take many pictures together. More than anything, we photographed Bologna and walked a lot, sometimes arm in arm.

Time was short, and there was so much to say. Even though we often keep in touch, great friendships, as you surely know, are creatures perpetually hungry for words.

We quickly brushed over professional matters to chit-chat about everything, as usual.

We are united by the care of an inner world we both built as children as a refuge from loneliness and a place of protection from the sharp edges that can hurt the soul. Over time, that space has become too an incubator for ideas that need time to ripen or storage for dreams that aren't yet ready to be dreamed.

In Amanda's case, it was an illness, dyslexia, the cause of Big Ben, that gave rise to her secret world where a confused little Amanda could do, speak, read, and learn without daily difficulties. I learned what dyslexia is with her even though I know something of that challenge, having lived with someone who encountered a similar obstacle.

Among the various things Amanda does, she writes an exuberant and poetic newsletter in Italian that is both practical and interesting. It weaves together many themes and different layers. The backdrop is her gentle, exciting, and authentic world. Reading it is beneficial for anyone who does. It lifts layers of anxiety from me, leaving my mind lighter and my horizon clean.

Let's give you a look at it.

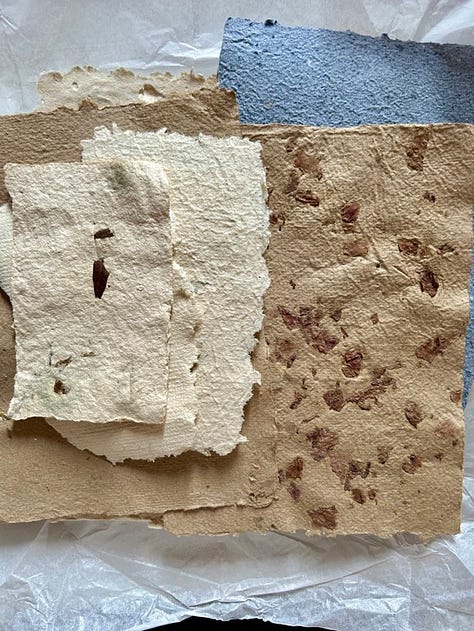

Amanda brought me some gifts: eggs from her chickens and beautiful paper she made herself. Each sheet is unique, and if I didn't have terrible handwriting, I would follow her advice and use it to write down some recipes by hand, just like they did in the old recipe notebooks.

The invisible network of women before the web

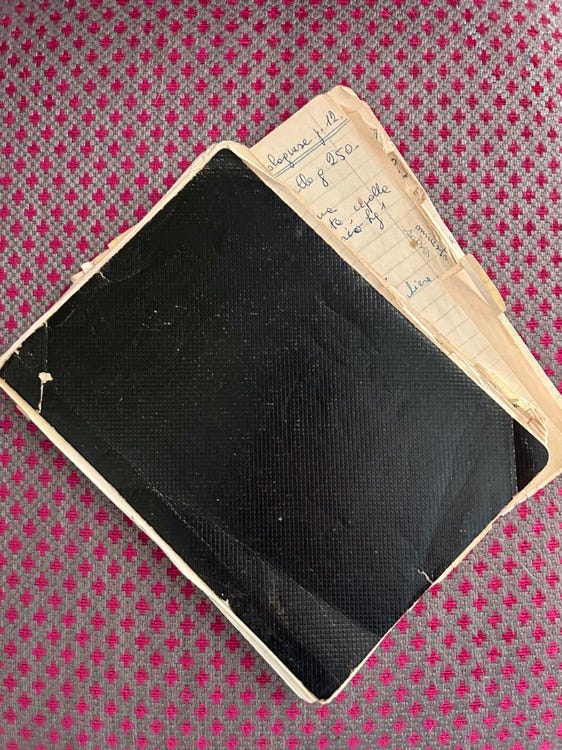

Women in the early 1900s didn't have the Internet or social networks. Nevertheless, their notebooks were a wide-open door to the world and held surprises, whether they contained notes written in clear and beautiful handwriting by women from the high society or uncertain characters in the handwriting and form by low social class women who had received an elementary education. And they were already one step ahead of all the others who were completely illiterate.

For these reasons, we may mistakenly think that the domestic cookbooks of upper class girls are a journey through sophisticated family, regional, and international flavors, and those from peasant or working class cuisine are merely collections of strongly local recipes.

True and wrong.

Without going too far back by quoting cookbooks based on antique gentlewomen correspondence exchanges, women born between the 1910s and 1930s, even from lower social classes, created a network by exchanging recipes through letters.

It all started with a news heard or reported that sparked curiosity, a sign of intelligence, and a thirst for life. Knowledge and exchange were entrusted to a sheet of paper. Thanks to a missive, they shortened enormous distances discovering new flavors and ingredients.

Due to a strong wave of internal migration in Italy after the end of World War II, my maternal grandmother came into contact with women from other regions who moved from the South to the North. Each had a relative left at home to whom to ask for this or that recipe. This is the only way to explain the Cassata Siciliana in the notebook that Grandma prepared for her daughter, my mother.

Unfortunately, we lost her letters. Nevertheless, the connection I mentioned emerges from the few that survived. These women deserve credit for circulating local recipes beyond the borders of their country and region, providing an undeniable contribution to the creation of a cuisine that evolved from regional to Italian.

Within a decade, the telephone became a new vehicle to support that network, speeding up the communication. I still remember my grandmother sitting by the phone, taking notes on anything she had, even the envelopes from the last letter she received. While we access the Internet, they build their own network.

However, I take comfort in the thought that something from those ancient female pioneers survives whenever we exchange a homemade gift or write a recipe on paper.

The Network

The Internet, accessible to a broad audience, is a relatively recent phenomenon, and the rise of food bloggers and food writers only began in the 1990s.

Among the pioneers are David Lebovitz, Jim Leff, and Bob Okumura (creators of Chowhound). In 2005, the first successful Italian blog was Il Cavoletto di Bruxelles by Belgian Sigrid Verbert, followed the next year by Italian Sonia Peronaci, creator of Giallo Zafferano. This platform brings together many food bloggers under the same brand and is now part of the Italian Mondadori group.

Recently, historian Massimo Montanari identified Pellegrino Artusi as the first Italian food blogger. Indeed, the Romagnolo gastronomist published an original and innovative book for his time, including recipes readers sent in. However, the absence of the Internet, a defining characteristic of a blog being an online platform, represents, in my opinion, a stretch in categorizing a 19th-century author in this way.

It brings me back to the paper and the women who sent a family recipe to someone they didn't know and would never meet.

The cookbooks before the Internet

With a few significant exceptions, most cookbooks published before 1900 were written by men for other men. Historically, everyday cooking was a woman's job, while that created to satisfy the sight and palate of nobles, princes, and popes was reserved for chefs who were always men. This is the art being published.

Women, who for centuries lovingly nurtured by bringing ingredients and lives to bloom, passed knowledge and recipes orally to the next generation. This predominantly oral transmission was also favored by illiteracy, which remained a reality for many women until the mid-20th century.

In Italy, we have no records of cookbooks written by women in ancient times, unlike the one attributed to Philippine Welser, which documents the culinary traditions of the German area. The unpublished manuscript is dated 1544-1545 and contains 200 recipes. At the time, the author was 18 years old. Many believe that the young woman was more of the recipient than the author of the book, which was likely commissioned by her mother for her daughter of marriageable age.

Even the notebook with the black cover written by my maternal grandmother bears my mother's name, the person for whom it was written.

The first German printed cookbook was written by Anna Wecker (1597). In it, the author collects recipes for elaborate dishes, everyday meals, quick recipes, and advice for less affluent families. In 1670, Hannah Woolley published a book in Great Britain with instructions for landladies and culinary tips.

It's also interesting to mention the structure of the recipes in these old books, where the ingredients are mentioned in the procedure without providing any information about the quantities.

Two women were important in breaking this mold and bringing cookbooks into modernity: Eliza Acton, Modern Cookery for Private Families (1845), and Isabella Beeton, Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management (1861). Both offer recipe texts with the list of ingredients and quantities separated from the procedure.

Reading tip

I loved Miss Eliza's English Kitchen. A novel of Victorian Cookery and Friendship by Annabel Abbs (2020).

Gradually, over the twentieth century, the rise of the bourgeoisie and increasing female literacy led to the establishment of a new type of gastronomic publishing based on a cuisine that was 1) economical and homemade (simple and robust dishes); 2) healing, with recipes for broths and soups to invigorate body and spirit 3) seasonal, on which events and religious precepts exerted considerable influence.

"Standing in the center of a kitchen, everything starts over, and something comes back" (by the Italian food writer Imma Fiorino). I learned it when I started cooking. I was hit by a wave of memories and knowledge that I had forgotten and, in some cases, did not even know I had learned.

Crostini Misti

I return from this brief journey into the past dedicated to ancient cookbooks and the rise of the Internet with a contemporary yet antique recipe that celebrates the goodness of bread and the embrace between the seasons.

It's old because the practice of using bread croutons to accompany soups dates back to the Middle Ages when sopa or supa in archaic Italian was one of the main dishes in the daily diet of the poorer classes. It's contemporary for the cheerful conviviality that a platter of crostini misti brings to the table. Sharing food from a single large pot, cutting board or tray is another aspect that harkens back to the past.

Crostini are both toasted cubes of bread or slices of bread. The difference between crostini and bruschetta is that the former are smaller. The slices do not have to be toasted before and then topped but seasoned, not just with oil or oil and garlic, I mean covered with something and then baked.

Among the flavors I've chosen to top the slices of bread, you'll find a symbolic hug between winter vegetables and the springtime delicacies to which, for once, I have yielded. So, alongside pumpkin, turnip tops, leeks, and cavolo nero, you will also find arugula and tomatoes. Mushrooms and ricotta complete the assortment of my crostini misti.

This dish can be prepared with your favorite ingredients, and the quantity is by eye.

Below are some tips I hope you find helpful for organizing an appetizer, brunch, lunch, or crostini misti evening for one person or many:

If it's a main dish, plan for 3 to 5 croutons per person

A loaf of about 700 grams should be enough for at least 8 people

Slice the bread thinly

Spread the slices with whatever you like: vegetable creams, cured meats, cheeses.

To make things easier and offer various flavors, prepare 3 to 4 different vegetable spreads you can use as a base, changing the toppings. If you stop at two, it will still be okay.

If you're making crostini misti for just a few people, use a small quantity of each ingredient and store any leftovers in the fridge for other uses, such as dressing pasta or making a torta salata.

I usually make that dish after my weekly vegetable shopping, so I can use small quantities of many different vegetables.

Crostini Misti by Monica

Some veggies are baked (squash, leeks, and tomatoes), others boiled (potato, turnip tops/cime di rapa and cavolo nero).

I cooked the leeks with salt, olive oil, and oregano in a covered baking dish and in a preheated oven until soft (I mashed them with a fork).

I blended the cream of cime di rapa and tomatoes with about 50 g of boiled potato.

Creams I used to spread on bread:

turnip tops/cime di rapa (I used stem, leaves, and some florets, potato, olive oil, salt)

tomatoes (I used baked tomato, pulp and skin, potato, oregano, olive oil, salt)

baked pumpkin stirred with salt, olive oil

ricotta, mixed with salt and olive oil

On the bases (slice of bread+cream), I added:

slices of mushrooms cooked in a pan with salt and olive oil

boiled cavolo nero leaves lightly toasted in pan to make them crispy

fresh arugula and stewed leek

ricotta quenelles and stewed leeks

cime di rapa florets and leek

On the crostini, I added grated Parmigiano in generous amounts. Then, I placed the pan in the preheated oven (200C or 392F degrees) for a few minutes.

If you have any questions about the preparations, I'll be waiting in the comments. You will receive my newsletter next Monday. In the meantime, make hearts and comments bloom and share.

Grazie, Monica

Let’s keep the conversation going.

Write to me at tortellinico@gmail or follow me on Instagram.