The Italian rituals of the summer solstice and St. John's Eve

Rural habits and recipes: San Giovanni's water, Nocino liqueur, and tortelli di erbetta

Hi, I'm Monica, and this is Kitchen Notes from Bologna, a newsletter featuring recipes, memories, food history, and bites of Via Emilia. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The summer solstice, which falls between June 20 and 22, marks the official start of summer and is also the longest day of the year, as the sun reaches its highest point in the sky. On that day, June 24, the Catholic calendar also celebrates the birth of Saint John the Baptist, ascetic and cousin of Jesus, not to be confused with John the Evangelist (December 27).

The summer solstice and St. John's Eve, although distinct on the calendar, are two events that are closely related in Italian popular and rural culture, given that in Catholic hagiography, the saint, who embodies the vital force and regenerative power of nature, is now the focus of new celebrations that have absorbed the previous pagan ones.

The night of St. John, between June 23 and 24, is considered magical, infused with the solar energy released by the solstice. At the same time, through his figure, a celebratory syncretism has taken shape where fire, water, herbs, flowers, and food are the protagonists of ancient rural rituals that have interlaced with Christian devotion.

This flavorful mix of sacred and profane rituals continues to characterize our times.

The rituals

The beginning of summer has been celebrated since the dawn of time when the ancients welcomed the triumph of light and the rebirth of nature. With the advent of Catholicism, many of these cults and their rituals were absorbed and renewed.

In this way, that complex of ancient rituals, including food rituals, previously linked to the solstice, has been passed down to us. On the other hand, the solstice represents a transition, a changing of season, which, in the agricultural world, which was predominantly agricultural in ancient times, has a significant meaning and strong symbolic value.

The new season is welcomed by the gentle spring, which opens the doors to summer, bright, exuberant, and excessive. And yet, it is precisely at the moment of maximum brightness that the days gradually shorten, preparing for the return of darkness. The seasons, both on the calendar and in life, never stop holding hands.

The rites that unite Italy from south to north include:

the recipes in honor of Saint John;

the nighttime bonfires;

the harvest of un-ripe, green, still soft walnuts with aromatic notes right for creating a digestive with an evocative flavor;

the harvest of herbs and flowers;

the collection of St. John's dew and purifying baths.

According to popular belief, fire and herbs are believed to keep demons and witches away, while purification rites with the blessed (and somewhat magical) water of San Giovanni are said to overcome bad luck and the evil eye.

Furthermore, in the past, girls would put flowers and herbs under their pillows to dream the face of their future husbands, while older people would roll on the grass wet with night dew to cure rheumatism. The "baptism of St. John" in the sea simulated a baptism.

The food inspired by Saint John the Baptist symbolizes the protection and fertility of the earth. Although the good Saint John, when he was not fasting, fed on insects and honey. Finally, ironically, once he died, his head was placed on a plate to please Salome.

In this newsletter, you will find a handful of memories, the ritual of the bouquet of St. John, and two recipes: Nocino, an ancient liqueur typical of the Via Emilia, and tortelli d'erbetta, according to the tradition of the city of Parma.

June, the month of the wonders

Perhaps not for my father, as I will explain shortly.

For me as a child, June was the month of the wonders because it brought the things I loved most.

Cherries picked by Maestro Nalon directly from the tree in the elementary school garden; evening walks in front of my house with my friend Claudia, both of us pushing our dolls in their strollers; lunches in the countryside with tagliatelle and crescentine (a typical Bolognese-Romagnolo fried bread); the scent of linden trees in the early morning; the veggies I ate in the garden after quickly cleaning them on my shirt.

June finally marked the start of gelato season and our move to the beach with our grandmother and aunt.

This move made my father a little nervous each time, as he spent hours trying to find the perfect combination of suitcases, objects, and people to cram into the limited space of our small family car, a glorious Fiat 128. Today, it is one of the family memories that provokes the most laughter. And, for me, a great deal of tenderness. Anyway, if you've never seen five people, a birdcage with its habitant, pots, toys, pillows, food, and suitcases inside a walnut shell, you've missed out on something.

In any case, before leaving, there were other things I loved of June. Namely, the rituals and preparations connected with the celebration of the solstice and St. John's, such as dinner in the countryside, eating al fresco under the porch of the farmyard, waiting for the bonfires, the preparation of St. John's water and Nocino.

The night of the basins and the holy, or magical, water of San Giovanni

The bouquet is composed of flowers and herbs: St. John's wort, mugwort, rue, verbena, lavender, garlic, onion, rosemary, mallow, yarrow, rue, fern, and mint.

The night between June 23 and 24 is the night of the basins on the windowsills. St. John's herbs are left to infuse in water until the following morning. The basins must be placed on a windowsill or outside the house to collect the night dew, as the saint's dew has healing properties.

If you live in the countryside, place the basin high up. Just so you don't end up like Mrs. Giulia, one of my grandmother's neighbors when she lived in the countryside, who used to say that her skin was glowing thanks to the dew of St. John. Still, then I discovered that no one had ever told her that Arturo, Egisto's dog, the chimney sweep, added a few drops of a certain elixir every year to her water put on the floor closed to door.

Depending on where you live, the flowers and, therefore, the composition of the bouquet can change. Of course, you can also personalize it by choosing herbs and flowers according to their meaning or properties. Certainly, St. John's wort, also known as St. John's herb, cannot be missing.

The bouquet should consist of 6 to 9 herbs. Or so I've been told.

On the evening of the 23rd, place the bunch in a bowl of water and put it outside so that the herbs are exposed to the night dew. The following morning, use the water to rinse your face: it protects and leaves your skin glowing and fresh. First, check that there is no Arthur around.

The ritual food of St. John

Because food always has something to do with St. John. As with many other saints, even though they were ascetics and fasters.

In any case, St. John is the saint who, more than any other, inaugurates the season of outdoor dining.

Depending on the area of Italy, people eat snails (cooked according to different recipes and local traditions), tortelli d'erbetta (ravioli with herbs), savory rice cake, stockfish, fava beans, rice or asparagus fritters, even elderflowers fritters (which, when picked on the eve of the feast, protects against theft, bad weather, and evil spells), and sweet almond cakes.

Other European countries also celebrate the solstice. The festival is significant in northern countries where there is little light for several months of the year. Rural rituals everywhere encompass even traditional recipes.

Along the Via Emilia, Parma's tortelli di erbetta and Nocino are two culinary traditions associated with the celebrations of the saint.

To make Nocino you need un-ripe and green, but already formed, fragrant walnuts. San Giovanni’s eve is the perfect time for harvesting them, as Artusi also points out in the introduction to recipe no. 750 - Nocino.

Of course, climate change affects the growth and ripening processes of traditional fruit trees. Today, the harvest of the un-ripe, green walnuts may be earlier or later than June 23.

In any case, there is a way to understand if the walnuts are ready: you need to be able to insert a needle or pin into the green shell without difficulty. If it goes through, they are ready, and you won't run the risk of making a green and bitter liqueur.

You can indeed find them by asking walnut tree owners directly or by checking out farmers' markets.

The origins of the recipe are ancient and uncertain. Of French origin, it may even date back to the Britons. Indeed, in Italy, the recipe has been known in the Modena area since the 16th century.

However, the first written version of the recipe refers to a walnut ratafia that appeared in 1766 in the text Il cuoco piemontese perfezionato a Parigi (The Piedmontese Cook in Paris), written by an anonymous author.

The production of a liqueur similar to today's version, known by its current name, Nocino, dates back to the period between 1860 and 1867 when Ferdinando Cavazzoni, butler at Casa Molza, included the recipe for the liqueur known as Nocino in his recipe book dedicated to specialties from Modena.

However, this liqueur, which originated as a digestive and panacea, is typical of the Italian countryside where walnuts and walnut trees are found.

My first Nocino

A few years ago, my husband and I made walnut liqueur for the first time, following a family recipe. In Emilia-Romagna, this liqueur is extremely popular, and I grew up watching and helping to make a variety of liqueurs, juices, and syrups.

What I didn't remember was how dangerous green walnuts are.

Don't forget to wear latex gloves, as the broken green walnuts stain your hands. My husband's hands were stained for a whole week!

Returning to the recipe, every family has its own. Some add certain spices, while others add more or less sugar. Some people stir or even mix the contents of the jar during maceration. In contrast, others would never dream of touching it.

Here is the recipe I have tried and, over time, have come to use.

The quantities are sufficient to produce several bottles, which will be ready around Christmas for tasting and gift-giving. Once bottled, this liqueur needs time, from a few months to a year, to develop its full flavor.

Nocino has a dark color reminiscent of dark chocolate. It has a sweet taste but is also balsamic and rich in nuances. Serve it after dinner as a digestif. In summer, add a twist of lemon and an ice cube.

Nocino

The Recipe

Equipment: latex gloves for kitchen use; a 2-liter capacity jar with cap

for a few bottles

Ingredients

700 ml of water

700 g of caster sugar

30 fresh walnuts with green hulls

1 liter pure grain alcohol (95% alcohol)

1/2 organic lemon, zest fillets

2 cinnamon sticks

10 cloves

Method

Put the water in a saucepan and bring to a boil. Turn the heat off, pour the sugar, and dissolve it stirring.

Let the syrup cool.

Meanwhile, protect your hands and cut the walnuts into 4 parts. You can use a cleaver-type knife or, more conveniently, a nutcracker (if you break the walnut, don’t matter).

Put the walnuts in the jar, then pour the alcohol, sugar-water syrup, and flavorings.

Seal the jar tightly and store it in a dark, cool spot in your pantry or closet. Let the Nocino age for a tantalizing 40 days, allowing the flavors to meld and deepen.

Sugar tends to crystallize and, therefore, end up at the bottom. Once a week, move the jar vigorously or stir the liquid with a spoon.

After the rest, strain and taste. If it seems too strong, add 100 ml of water once or twice (to your taste). Stir and bottle.

Taste after a few months. Store in the pantry.

Tortelli di erbetta

It is a specialty of early summer. In the Parma area, this dish is traditionally served on the evening of June 23, the eve of the feast of St. John the Baptist, to welcome the cool night air full of dew. Even in the city, people move the tables to the streets of the downtown and gather to eat together.

The dish was created to celebrate the eve of a feast day and is, therefore, meatless.

Spinach is the main ingredient of the filling of these square or rectangular tortelli.

Although they are almost always referred to as tortelli di erbette, at the plural, only one green herb is used in the filling. Hence, tortelli d'erbetta. In the past, Buon Enrico, a local wild herb similar to Swiss chard, was used. Today, Swiss chard or spinach are usually used.

In Mariangela Rinaldi's book dedicated to the correspondence of the Parmesan aristocracy between the 19th and 20th centuries, we read:

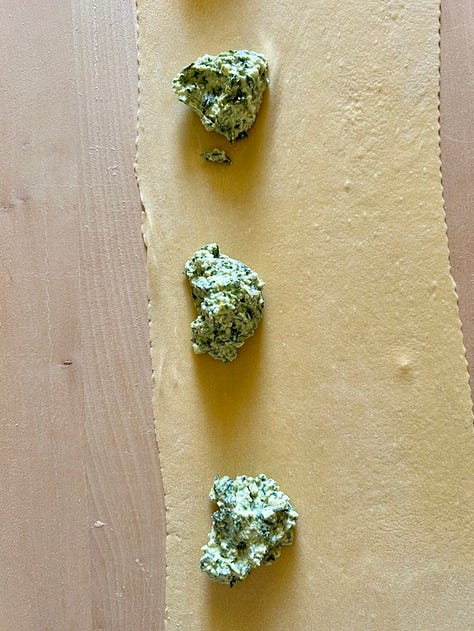

The rectangular tortello is made from a thin sheet of dough. The filling is a delicious mixture of ricotta cheese, eggs, Parmigiano, chopped herbs (hence the name), and a thought of nutmeg.

And on that thought of nutmeg, I sighed first and then began to make the pasta dough.

I seasoned tortelli d’erbetta according to tradition, that is with lots of butter and grated Parmigiano, which, as popular folklore says, should be drowned in butter and dried in cheese.

Tortelli d’erbetta

The Recipe

4 serves

Ingredients

Filling

300 g of cow's ricotta cheese

100 g of grated Parmigiano

350 g of fresh chard or spinach

1 regular egg

1 g of nutmeg

3 g of salt

Pasta dough

300 g of 00 flour

3 regular eggs

Instructions

Filling

Clean the vegetables, boil them in unsalted water, drain, and let them cool for about 30 minutes before squeezing the leaves. Then finely chop it with a knife.

Combine and mix all the filling’s ingredients with a fork in a bowl. Cover and let stand for 2 hours in the refrigerator.

Pasta dough and sheet

Place the flour on the cutting board and form a well in the middle with your fingers.

Shell the eggs in the well and beat them lightly with a fork.

Then, using your fingertips or a fork, gradually incorporate the flour into the well in a circular motion until large breadcrumbs form, being careful not to break the walls of the well and lose the eggs. In this case, use a spatula to stop the run.

From that point, knead the dough by hand on a clean surface until soft but firm, about 10 minutes.

Cover the dough with a bowl or wrap it in plastic wrap and allow it to rest at room temperature for at least 30 minutes to several hours. If storing overnight, refrigerate and bring back to room temperature before use.

After resting, lightly flour the cutting board and dough to prevent sticking.

Place the pasta dough in the middle of the cutting board and place the rolling pin in the center of the pasta dough. Then begin to roll as you would a sheet of shortcrust pastry, working from the center.

Every 2-3 strokes of the rolling pin, rotate the sheet 45 degrees to give it an even shape (round or oval). As the sheet becomes larger, don't fold it. Wrap it around the rolling pin to rotate it without breaking the sfoglia.

Continue to roll from the center outwards, then back to the center. Hanging the sheet over the edge of the table will help stretch the dough. Always turn the dough sheet 45 degrees (do this by rolling the pasta sheet around your rolling pin and turning it) and continue to roll until you have achieved a perfectly smooth sfoglia sheet.

Roll out a thin sheet of dough.

Tortelli assembling and cooking

Cut out strips of pasta sheet 6-7 cm wide, then place one tablespoon of filling every 3 cm. Fold the pasta sheet back on, press gently around the filling to let the air escape, and use a pasta cutter wheel to cut out the tortelli. If there is too much excess sfoglia along the edges, remove it by cutting it away.

Dry the tortelli on a floured tray for 30 minutes to an hour, turning them over occasionally.

Bring a pot of water with salt to a boil. Add in tortelli and cook for 5-6 minutes.

While the tortelli are cooking, melt plenty of butter in a pan.

Arrange half the melted butter on the serving dish and sprinkle with Parmigiano.

Then, using a slotted spoon, remove the tortelli from the boiling water and place them on the dish. Cover them with the remaining melted butter and as much Parmigiano as you like.

Food tips

Store any leftovers in a covered dish in the refrigerator for a couple of days.

If you want to freeze the pasta for later use, let the tortelli rest outside the refrigerator for 30 minutes. Then, blanch the pasta for 2 minutes, drain, let it cool, and use fingers greased with olive oil to lightly rub the tortelli so they don't stick. Freeze. When ready to use, cook them by dipping them in boiling, salted water.

June started like a tornado.

So many things to think about, do, and organize. Still, there's time for another newsletter before the month ends (with something special on fresh pasta for paying subscribers). With the next one, I'll kick off a series dedicated to women and cooking.

If you're interested in the topic, you're in the right place.

And spread the word.

Ciao, Monica

This is so, so beautiful. Thank you for sharing it! It brought me right to your memories.

I love hearing about these lesser-known (outside of Italy) rituals and traditions - thank you for sharing so generously!