What is the origin and meaning of the nicknames that define Bologna?

You could consider this newsletter as a test and, at the end, write to me in the comments if you knew and attributed the correct meaning to them.

The meaning of the Felsinea and the Turrita

The ancient Etruscan name for Bologna was Velzna or Felzna, meaning fertile land. Felsina is the name Latinized after the arrival of the Romans, and the adjective felsineo/a, which is used as a synonym for Bolognese, also descends.

The Romans then changed the name of the city to Bononia.

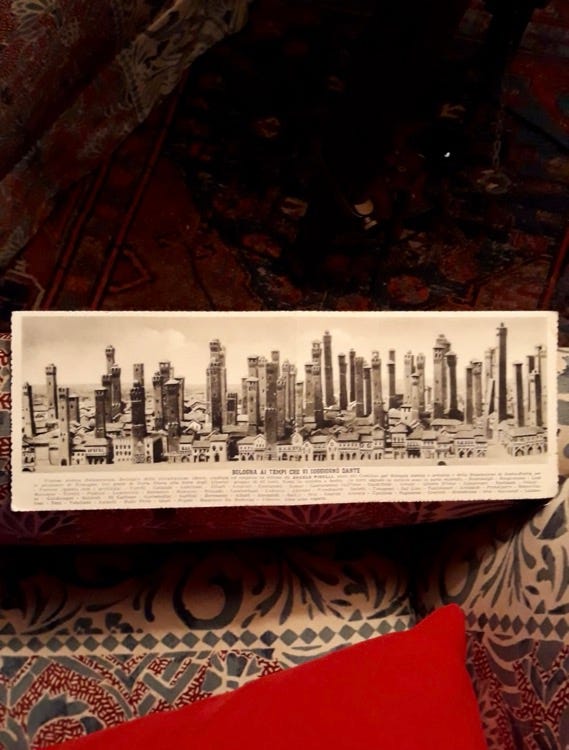

In later times, beginning in the Middle Ages, Bologna's skyline resembled today's Manhattan. It was dominated not by skyscrapers but by more than 100 towers built by the city's most influential families with a primarily military function.

In the period of opposition between the factions of Guelphs and Ghibellines, the former supporting the Church and the latter the Empire, towers were lookout points and fortified bulwarks for defense and offense.

Their importance diminished after the struggles between the Guelphs and Ghibellines ended. Over the centuries, many were torn down to permit a city redevelopment in modern key.

Today, about 30 remain. Also the name The Turrita (with many towers) persists.

Bologna The Learned (La Dotta)

It seems unbelievable, but it is true. In the medieval Italy of the Communes, which succeeded the Roman Empire, the University was born before the municipal institution of Bologna.

The founding of the Municipality of Bologna dates back to 1116; that of the Alma Mater Studiorum, the University of Bologna, to 1088.

The nickname is linked to the presence of the oldest University in the Western world. However, there is an aspect less known in its origin that makes it unique and special.

The date 1088 is fictitious but plausible. The Studio did not come into being due to the edict of a sovereign or by the decision of a political or religious authority.

The University of Bologna emerged spontaneously through the initiative of the students, who decided for themselves which teachers to call and paid them out of their own pockets around 1088.

The city authorities immediately forged a powerful bond with the Studio, which increased the city's international prestige and attracted a considerable flow of people.

Around 1118, Bologna was already known as The Learned and, about a century later, The Fat.

The Archiginnasio, now a public library, is one of the oldest sites of Bolognese scholarship. Its frescoed walls show the family crests of the many students who passed from here.

Bologna The Fat (La Grassa)

The intellectuals of the Middle Ages created an unbreakable link between Bologna The Learned and Fat. At that time, the city was a small medieval metropolis surrounded by fertile countryside and waterways and already characterized by flourishing trade. These factors guaranteed the presence of food and supplies.

The Studio quickly achieved fame with this richness, which makes life pleasant for scholars and visitors. Spreading its gastronomic fame are students and professors who bring back a distinct image of Bologna to their homeland as they move back from one end of Italy and Europe to the other.

The appellation, The Fat, probably takes shape in France. For the historian Massimo Montanari, it is not demonstrable that Paris is the place of invention of the Bolognese myth, but realistic because in French documents are the oldest texts in which, from the early thirteenth century, we find the term "la craisse Boulogne." At first, the epithet probably wasn't flattering. In fact, the Parisian jurists suffered the competition of the the Studio Bolognese, which attracted an increasing number of students.

The label started to appear from the 14th century even in non French sources.

As other Italian universities emerged, propaganda to attract students and professors found a mainstay in the theme of food resources. When Frederick II of Naples founded the University that still bears his name in 1224, he wrote that "everything necessary comes there (Naples), by land or sea."

The second nickname, widespread since the 1200s, clearly does not refer to twentieth-century dishes such as cotoletta alla Bolognese, seven-layers green lasagna, and ragù.

So what was eaten at that time?

For sure, the mustard of Bologna (the recipe is on the blog). In 1487, it even appeared on the menu of Annibale II Bentivoglio, Lord of Bologna, and Lucrezia d'Este's wedding banquet.

And, of course, the Torta di Riso (the recipe and history are on the blog: HERE). It’s a sumptuous Bolognese cake created for the celebration of Corpus Christi.

Bologna The Red

The nickname refers to the shades of red that have characterized Bologna's roofs since ancient times and that, at one time, we would have admired from the top of all the tallest towers. Today, you can observe this sight from the Torre degli Asinelli (when it will reopen), a building that bears the surname of the noble Bolognese family that erected it.

Did you enjoy this newsletter?

This and that

About Pasta

If you visit the Archiginnasio through Dec. 7: Pasta. Fresh, dry, colored, and filled. Free event; check hours HERE

Flood

Poor Bologna! The most recent flooding has caused big damages in the city and the surrounding area. The dog house in Sasso Marconi, from where Lillo comes, was washed away. They need an help to rebuild it. Many people from abroad are helping those poor dogs. Together, we can make a difference. I'll leave you the link for the fundraiser: HERE.

See you soon. Ciao from your cookery writer!

Let’s keep the conversation going.

Write to me at tortellinico@gmail or follow me on Instagram.

If you enjoyed this newsletter, please click on the little ❤️ below ⬇️ and

Thank you Monica. This was a great read and a beautiful view of your city. I am so sorry to hear of the devastating floods.